Louis Theroux on The Ultra Zionists

Louis Theroux – The Ultra Zionists

Aired 2nd February 2011 on BBC Two

Plus Louis Theroux: My time among the ‘ultra-Zionists’, 3 February 2011

Louis Theroux spends time with a small and very committed subculture of ultra-nationalist Jewish settlers. He discovers a group of people who consider it their religious and political obligation to populate some of the most sensitive and disputed areas of the West Bank, especially those with a spiritual significance dating back to the Bible…

Louis Theroux: My time among the ‘ultra-Zionists’, 3 February 2011

Louis Theroux spends time with ultra-nationalist Jewish settlers and discovers a small, but very committed subculture.

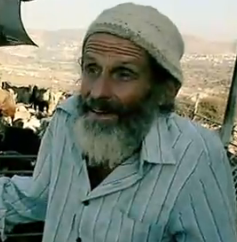

On a hilltop in the Northern West Bank, not far from the large Palestinian city of Nablus, I met 17-year-old Yair Lieberman.

A part-time labourer and student, Yair’s home was a makeshift canvas-covered structure, only slightly more solid than a tent, which he shared with three other young men. The bed was a tangled mess of sheets, in the style of a conventional teenager’s, and hung around the dwelling were posters – though not of pop groups, but of favourite rabbis. Outside, in the neighbouring lots, was a scattering of fifteen or so caravans and trailers – the outpost of Havat Gilad.

Like the settlements up and down the West Bank, Havat Gilad is illegal under international law. It lies miles inside the territory won by Israel in the 1967 war and the vast majority of the surrounding population is Palestinian. But Havat Gilad is also illegal under Israeli law. Electricity comes from a generator. Water is trucked in.

Yair moved up to Havat Gilad a couple of years ago. On a tour around the hilltop, I asked him why he’d decided to make his life in this ramshackle encampment, at the end of a dirt road, on an inhospitable hilltop among Arab olive groves.

“If we’re not here there’s a [Palestinian] city and we don’t want another [Palestinian] city,” he said.

What, I wondered, would be so bad about another Palestinian city?

“Because it’s my land! It’s the land of Israel. It’s not the land of Palestinians.”

Yair’s beliefs are shared by a hardcore religious nationalist fringe of Jewish Israelis who have chosen to make their home up and down the West Bank and in East Jerusalem. They say that those areas belong by right to the Jewish people – a title claim based mainly on the bible.

The fact that there are nearly ten times as many Arabs as there are Jews in the West Bank, with their own dreams of a national homeland, they regard as a side-issue.

I was making a documentary about these ultra-nationalist Jewish settlers, called The Ultra-Zionists. For several weeks I’d been spending time in some of the most hardcore and uncompromising sections of the Israeli nationalist community – the Jewish enclave in Hebron, in the hilltops in the north of the West Bank, and in the crowded Arab neighbourhoods of East Jerusalem – choosing to come at a time when peace talks were ongoing and the extreme settlers were therefore more embattled.

For many years I’d been fascinated by extreme nationalists – and I’d hoped the issue of the West Bank and its settlement by extreme religious Jews would be a chance to understand this mindset at first hand.

The day before meeting Yair I’d travelled up to the nearby outpost of Givat Ronen, known to be, if anything, an even more radical and nationalistic community. Early that morning I’d learned that the Israeli army had taken the fairly unusual step of actually enforcing the law against the extreme settlers and dismantling a small house and a goat shed.

Given that the whole community was illegal under Israeli law, the army’s action was somewhat tokenistic. But even this was enough to set off local Jewish settler youths who reacted by stoning the shops in a nearby Palestinian village and setting fire to the hillside.

It might be easy to write off these “ultra-Zionists” as people on the fringe of a fringe in terms of their outlook and beliefs. And it is true that many, if not most, Israelis say they would be happy to pull out of most of the occupied territories if they were confident it would lead to peace.

But what makes the extreme settlers more troubling is that they also enjoy a degree of support from the Israeli state. Surprising as it may seem, many illegal outposts like Yair’s are protected by the Israeli army. And in East Jerusalem and Hebron the Jewish presence is fully legal under Israeli law and underwritten and guaranteed by a vast security force.

The anger and despair of the Palestinians at the settling of foreigners in their midst is palpable. Many say they would be happy to have Jewish neighbours but not while they don’t enjoy the same rights or have the same sovereignty. Towards the end of my stay, one of the settler security guards in East Jerusalem shot and killed a Palestinian man. Rioting was widespread and it seemed clear to me the country was close to a third intifada.

Not long after that I left Jerusalem, but not before I visited Yair again. Once again I found him friendly, likeable, and yet profoundly lacking in perspective of how his national aspirations were trampling on the rights of millions of Palestinians.

With the very vague possibility of peace on the horizon, I asked if he wasn’t worried about being told to leave.

“If they want they can take me by power and I’m going to come back illegally,” he said. “This is our land. You can come and kill us and do whatever you want. We’re going to die for this country.”